Let’s talk about Judah Maccabee’s dad

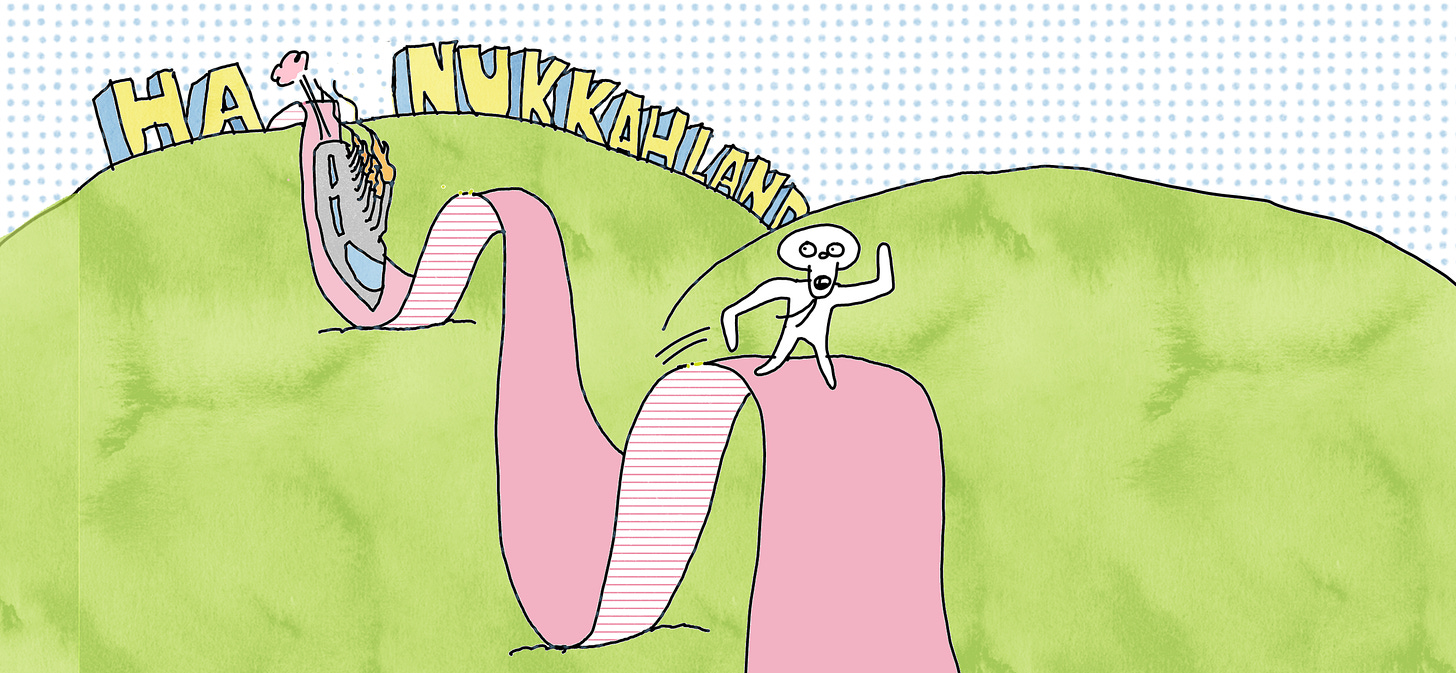

Also, news from HanukkahLand: Johnny Hanukkah runs the HanukkahLand monorail

IN WHICH:

My mother makes latkes for my entire classroom while I try to tell the story of Hanukkah.

The true hero of Hanukkah is revealed to be Mattathias, not Judah.

Ben Shapiro goes to school.

Johnny Hanukkah is revealed to be the true TRUE hero of Hanukkah.

1.

Every December between first grade and fifth, my mother would visit my classroom and make latkes. On the surface, her intention was to provide cultural enrichment to the community. Our town was split between Catholics and Protestants, meaning they knew nothing of Hanukkah.

Mom knew that the key to any culture was its food. On two desks joined together she balanced her Cuisinart, a plate of potatoes, and a hot plate with heated oil. Her vision was to process enough potatoes for fifteen children and intermittently explain the story of Hanukkah.

Except she didn’t know the story of Hanukkah.

“Sam, why don’t you explain the story of Hanukkah?” she said. I would try, but it was hard to be heard between pulses of the food processor.

“The Maccabees were a tribe of Israelites ...”

PULSE!

“But the Greeks burned down the second temple ...”

PULSE!

“Skip ahead to the miracle,” my mother said.

“I was getting to that,” I tried, but she didn’t hear me over the long pulse of a knotty potato. And anyway, the miracle doesn’t make sense unless you understand the history: the Seleucid Empire (who weren’t exactly Greeks), the survival of the Judeans (who were Jews, but only one kind ), the rise of the Maccabees (who weren’t exactly heroes, not to everyone), and if you’re going to get into all that, you have to cover Judah Maccabee, the most complex character of them all. He’s the closest we have to a Santa Claus, despite lacking all the cuddly, generous, electability of Santa. Judah isn’t even a folk hero, as some will claim. Though his father, Mattathias, certainly is.

2.

The Maccabean revolt was a revolt against a culture.

It began with Mattathias, a Jewish priest -- weird that they didn’t call them rabbis -- who refused to perform a pagan ritual. The particular ritual isn’t known, so let’s just say they wanted him to eat a ham and cheese croissant. Now, he could have simply refused to do it, but in the process, he also killed another Jew who agreed to eat the ham and cheese croissant. Less ironically and also a pagan priest.

This is the domain of the folk hero, the overcorrecting to make a statement. Mattathias’s statement, before running into the wilderness, was “Let everyone who is zealous for the Law and supports the covenant come with me!”

3.

The folk hero has a long history and many definitions, but the best one I can drum up is anyone who Ben Shapiro thinks is bad.

A perfect example is Luigi Mangione. If you haven’t followed the Mangione/Shapiro timeline, here’s a quick recap: days after Mangione was revealed as the suspect in the assassination of healthcare CEO Brian Thompson, Ben Shapiro released a video on YouTube criticizing the folk hero status Mangione has achieved, and the comments section was unlike anything Shapiro had ever seen:

This is better than latkes.

4.

Mattathias was able to gain considerable attention from hit-and-run attacks he incited on Selleucid (Greek/Syrian) soldiers, and gain quite a following, but the spree only lasted a year before he died. Before his death, he instituted a succession plan, installing his son Judah as the leader of the revolution.

Judah was a folk hero nepo baby.

5.

I realized we needed to find a better Hanukkah story. The old one is too bloody, too complicated, too Gladiator II.

I wanted something present. Something friendly. So I made one up.

“Johnny Hanukkah runs the HanukkahLand monorail,” I started.

6.

Johnny Hanukkah™ wakes up every morning because one of his three jobs is to run the MenoRail™, a monorail system in the shape of a menorah that serves all the people of HanukkahLand™. No one else in HanukkahLand knows how to do this and even though he keeps telling the mayor he needs to come up with a succession plan, the last thing that anyone wants to think about is the future. So for now, they’re stuck with this one single guy running the MenoRail, which everybody depends on in order to get the places that they need.

The MenoRail is run on burning wax, which is produced by the Whackabees™, which is a whole different issue I’m not going to get into right now.

Johnny’s situation is especially unfair because everyone in HanukkahLand works from home. He sees them taking video calls from their houses, laughing with their bosses about babies crying in the other room, dogs needing to be let out, packages being delivered all while they’re getting paid for sitting in their pajamas! Not fair.

When Johnny Hanukkah talks to his boss, it’s through a walkie talkie on the MenoRail, and usually he has something micromanagerial to say to him. “Did you print out the monorail schedule?” the mayor may say.

“No,” Johnny will say. “People can get it on their phones.”

“But I think it’s important for them to have it printed out,” the mayor will say, or something like it. “It’s a better customer experience.”

The mayor only cares about the customer. He doesn’t care about Johnny.

7.

One time the mayor and Johnny Hanukkah got into a fight about whether Die Hard is a Hanukkah movie.

“I’m telling you, it’s about a guy who overcomes an oppressive force and takes matters into his own hands.”

“This sounds violent,” said Johnny Hanukkah. “And you’re forgetting about the monorail.”

“Am I?” said the mayor. “Oh, you must mean the MenoRail™.”

“Yes,” said Johnny Hanukkah. “My customers are waiting.” He knew that would get the mayor to give him a break.

“Are you going to pick up those printed schedules?” asked the mayor.

8.

At this point, my teacher intervened. My mother had been long-gone and the latkes had been eaten. It was now the middle of March.

Endnote:

This jumping around, let’s talk about it.

Close to my home in Brooklyn there’s a small commercial district run almost exclusively by immigrants. It’s New York, so the variety of stores and ethnicities is something I’ve come to expect. I’ll buy gloves from a Korean discount store then walk across the street to drop off summer clothes at the Armenian dry cleaner. The stores themselves don’t stay consistent either, adapting to the neighborhood’s ever-changing story. What they all have in common is they do whatever they need to do to make it work. Earlier this year, I wrote about my barbershop starting to sell phone accessories. And just yesterday, I brought some leaky boots to what I thought was a shoe repair shop. I should have suspected something when the clerk took the boots and said, “Yes, I can do this for you.”

Of course you can, I thought. You’re a shoe repairman.

The store was closed when I came back to pick up my boots. The store owner next door, who was the real shoe repairman, told me the guy I gave my boots sells jewelry. “He takes my business,” he said.

Perhaps it’s a flaw of mine that I don’t question the strangeness of reality. When I encounter a jeweler who also repairs shoes, I think, Sure, why not, makes perfect sense to me. The same goes for the essays I’ve been writing recently. They shift and change. They pull from a variety of sources. They recolor according to my mood.

Thank you for reading this first Hanukkah essay. For the next seven days, if you join me on this journey through HanukkahLand, I will warn you about this jumping around. Excellent stories, fascinating takes, characters you can’t forget, one or two references to Jewish literature, all at the service (I think anyway) of figuring out what this holiday means to me. I call them microessays because they’re short. and although they won’t always follow a straight line, they always serve the story, and at least (once again) they are short. I hope you have as much fun reading them as I had writing them.

I am late to HanukkahLand…

Love this. And always our mom trying her best to teach inclusion.